Anglo-Saxon Wiltshire

The three centuries from the departure of the Roman legions at the end of the fourth century to the accession of Inc as king of Wessex at the end of the seventh are often called the ‘Dark Ages’. This is not just because the economy of the country started to revert to that of the Iron Age but more because our evidence for reconstructing the history of those centuries is scarce and weak. There is confusing archaeological evidence from the excavation of many early pagan Saxon graves; but it is extraordinarily difficult to date the timing of their parent settlements even when such sites are found, and more so to determine the newcomers’ relationship to the Britons of the area. There are few traces of early Saxon buildings and worst of all the written record is scant and wildly prejudiced.

The earliest written record is that of Gildas, the first British historian, a Romanised Christian monk who died about A.D. 572 and had seen some of the Saxon immigration. In his De Excidio Britonum he viewed the pagans with such horror and so vehemently criticised the petty kings of Britain for inviting for their defence the ‘fierce Saxons of ever execrable memory, admitted into the island like so many wolves into the fold’ that he cannot be trusted to have given a balanced account. He tells us of the battle of Badon, though without mentioning Arthur, where Britons defeated marauding Saxons, but writing from the Welsh borders he had no knowledge of peaceful settlement in eastern and south-eastern England.

Our next source is another West-Country monk (or monks) called Nennius, who collected fragments of British history in the ninth century. These tell us of the battle of Badon where Arthur, leader (‘dux’) not king of the Britons, won one of a series of 12 famous battles, the last being at Camlann where he was killed. Badon, which does seem to have marked a pause in Saxon movement westward, is now dated to about A.D. 495 and Camlann (probably in northern Britain) to 515.

The next record of Saxon activity comes from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is a record in Old English, and the first history in any native North-European tongue, of events from the birth of Christ to the end of the reign of King Stephen in 1154. It appears to have started as a church calendar of Easter tables with additional notes on special events, and to have been put in ordered form first by King Alfred of Wessex in the 890s. It has a strong Anglo-Saxon and Wessex, perhaps even Wiltshire, bias and entries up to A.D. 449 are very brief. That for 449 records that Hengist and Horsa, leaders of Jutes, were employed by Vortigern, but while it is known from the archaeological record that Saxons had long settled in the Thames Valley it is not for nearly another century that the Chronicle records a direct incursion into Wiltshire territory.

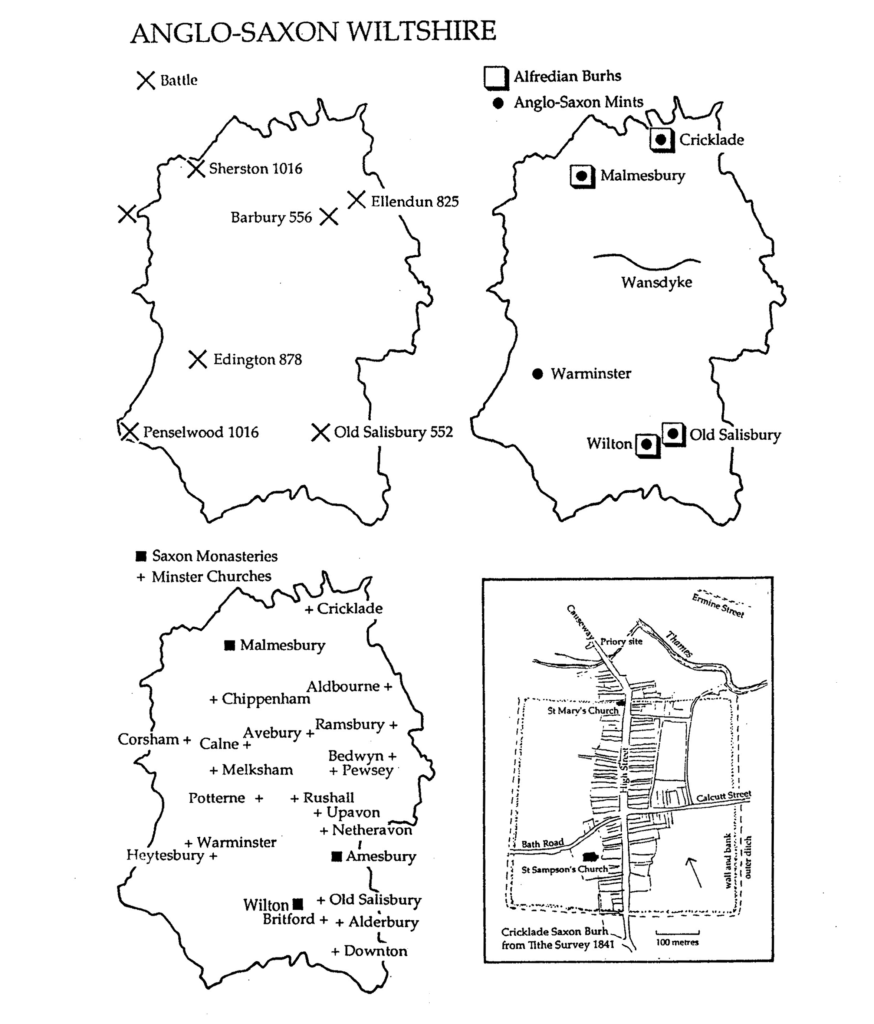

The creation of Wessex

In 519, says the Chronicle, Cerdic and Cynric ‘obtained of the West Saxons the kingdom’, which was based probably on the Roman sub-regional capital of Winchester. They conquered the area around Southampton Water and the Isle of Wight and then moved inland, defeating a British force at Charford on the Hampshire border. They defeated another British force at Old Salisbury in 552 but probably controlled southern and eastern Wiltshire before then, as many pagan burials predating the sixth century have been found around Salisbury.

In 556 Cynric went on to defeat another British force at Barbury Castle near Swindon. Four years later his son Ceawlin ‘succeeded to the kingdom of Wessex’, as the Chronicle calls it for the first time, and he extended the kingdom eastward into Surrey and then in 577 northwards, defeating a British force at Dyrham, a few miles north-west of the modern Wiltshire border, in a battle which enabled him to take the decayed Roman towns of Gloucester, Cirencester and Bath. The numbers involved in these battles were probably small, for Cerdic and Cynric came to England to carve out a kingdom with only five ships and perhaps two hundred and fifty followers, and even as late as the seventh century, in King me’s famous law code, ‘up to seven men were thieves, from seven to thirty-five a band, and above three dozen an army’. The battle was decisive, however, for it effectively cut off the Britons of the West Country from those of the Midlands and Wales, and prevented forever any concerted effort to drive out the more aggressive Saxons.

Ceawlin attempted to extend his power further north but, whether from meeting hostility from Saxon neighbours to the north and east or solely from a dynastic dispute, he suffered a defeat at Adam’s Grave, a prominent long barrow on the north side of the Vale of Pewsey, and was driven from his kingdom. This last battle was close to the longest ancient earthwork in the county, the linear ‘Wansdyke’, i.e. the dyke of Woden, chief god of the pagan Saxons. It runs 12 miles across east-central Wiltshire on the north downiand side of the Vale of Pewsey, from Morgan’s Hill eastwards to the edge of Savernake Forest two miles south of Marlborough. It has an impressive ditch and bank some ninety feet wide overall, with a few causeway crossings. In spite of a number of excavations it can only be dated loosely to between A.D. 450 and 600. It was long assumed to be a defence built by Romanised Britons, led perhaps by Arthur, against Saxons of the Upper Thames valley, but it now seems more likely that it was built by Ceawlin to anticipate an attack by northern Saxons. Its significance was short-lived and present parish boundaries, sometimes based on pre-Saxon estate limits, pay it no respect.

Leadership of the Saxon kingdoms then passed for many generations to those to the north, and it was under pressure from the kings of Mercia that Wessex was introduced to Christianity. St Augustine had been sent to England by the Pope in 597 to convert the country. His mission was successful and Christianity spread rapidly among the Saxons, though some, like Redwald of East Anglia, worshipped pagan gods simultaneously. In 635 Birinus, a Benedictine monk from Rome supported by the Mercians, was given the newly created see of Dorchester, Oxfordshire, and there baptised Cynegils of the house of Cerdic, now king of Wessex.

The son and grandson of Cynegils started a new period of Wessex expansion westward by defeating Britons at Exeter, and taking control of Devon, Somerset and east Cornwall as well as absorbing Dorset, so that Wiltshire was now the heartland of the kingdom. King me, the best-known of the early rulers, succeeded in 688. Apart from making the first laws for good government since the departure of Romans, laying down the blood-price for killing Saxons and Welshmen, as his British subjects were now known, me encouraged learning and the Church. He refounded the ancient monastery at Glastonbury and put in charge his talented kinsman Aldhelm, who had done so much to improve the abbey at Malmesbury. In 706 the Pope permitted me to divide the large see of Winchester, which had been founded in 662, into two, a new see being created round Sherborne for Wessex west of Selwood; Inc appointed Aldhelm as its first bishop. He went on to secure the submission to Wessex of London, Essex and Kent, and he defeated a Mercian invasion at the second battle of Adam’s Grave in 715.

Rivalry and disputes with the powerful Mercians continued for most of the eighth century; the marriage in 787 of the king ofWessex, Beorhtric, to the daughter of Offa, the greatest king of Mercia, was an attempt to heal the rift. But rivalry with Mercia continued in spite of the dynastic marriage, and a raid from Mercia across the Thames at Kempford in 802 was defeated by the ‘Wilsaetan’, i.e. the men of the Wilton or Wylye area, as the Wiltshire Saxons were called for the first time. After a further defeat at Ellandun near Swindon, in 825, the Mercians accepted the leadership of Wessex, as did the Northumbrians: all were now facing the considerable external menace of Viking raids.

The impact of the Vikings

Viking raids on the Wessex coast had begun as early as 787 but for long remained unorganised. The raiders gave little thought to settlement and had little effect on an inland county like Wiltshire. But in the next century, the ninth, increasing and more powerful raids were made across both central and southern Britain from which the raiders retreated to ships on the east coast as winter came on. They became a still bigger menace when they started settling in less-densely populated parts of East Anglia.

Sometime before the end of the ninth century Wessex was organised into shires, each under the leadership of an ‘ealdorman’ as the king’s representative, and each shire had its ‘fyrd’, a force of men subject to compulsory military service, at least within their own county. Alfred, of the house of Cerdic, was now in charge of an army for the defence of Wessex made up of these fyrds and dealt well enough with most of the hit-and-run Viking raids. In 878, however, when he had succeeded his elder brother to the throne, he was caught out by a Danish force led by Guthrum, who now controlled the old East Anglian kingdom. Alfred had chased Guthrum’s army from Wareham and Exeter and forced them to retreat into the Mercian town of Gloucester before he retired to spend a quiet Christmas at Chippenham. But Guthrum, instead of going back to Suffolk, ‘went secretly in midwinter after Twelfth Night to Chippenham and rode over Wessex and occupied it’ to quote the Chronicle. Alfred escaped with a few men through Seiwood to the Somerset marshes and prepared to reorganise his scattered forces. After Easter he called on the fyrds of Somerset, Wiltshire and east Hampshire to meet him at ‘Ecgbrytesstan to the east of Selwood’, probably the estate boundaries at Willoughby Hedge, near Mere. From there he went the following day to ‘Iley Oak’, the meeting place of a hundred near Longbridge, and the next to the edge of the downs at Edington near Westbury. Guthrum came out to meet this threat but was soundly beaten and after two weeks’ siege in Chippenham, surrendered, swore to leave Wessex for good and to receive Christian baptism. The dispirited chalk figure of a horse below Bratton Camp is probably a recut (and reversed) version of an early memorial to the battle.

Edington was not the end of Alfred’s troubles with Danes and he set about learning some lessons from them. First, he built a fleet to intercept Danish ships at sea and, second, he adopted the Danish system of forts and avoiding, where possible, pitched battles. In Wessex he made his forts into a network of small towns, no more than 40 miles apart, into which the local population could fly when threatened; these ‘burhs’ were planned as new towns with a commercial basis rather than as simple forts. Their fortifications consisted of a high bank surmounted by a heavy timber fence, surrounded by a ditch, their plan commonly being rectangular. Inside, building plots were laid out on a regular grid. Modern Cricklade still retains the layout of its Aifredian foundation. To ensure the upkeep of the burhs, special rates were levied on the surrounding population which were in proportion to the length of the defences in each case. Apart from Cricklade, burhs were established in Wiltshire at Malmesbury on the Avon-fringed spur where Aldhelm’s abbey was now famous, at Wilton and at Chisbury, near Great Bedwyn. At Wilton the burh was commercially successful but it was difficult to defend, so in times of stress its administrators and moneyers would move to the older fort of Old Salisbury; thus the two places acted in tandem. Chisbury was perhaps the inverse of Wilton for it was a small fort of only 15 acres, intended more for the protection of the important royal estate of Bedwyn. It certainly never became a market town as did its companion Bedwyn.

The Wiltshire burhs were given the right to mint their own coins, which helped to establish successful markets. The resultant stability in Wiltshire led to the development of other small market towns, such as Ramsbury, Bradford on Avon, Calne, Marlborough, Tilshead and Warminster. In 909 the first of these six was made the seat of a new bishopric, carved like Sherborne from the diocese of Winchester, to serve Wiltshire and Berkshire. It was as a consequence of these developments that Maitland could say of Wiltshire at Domesday that it was ‘quintessentially the county of small boroughs’, and that later it had a disproportionate number of seats in the king’s parliament.

Alfred was the first English king to fight the Danes to a standstill, work that was continued by his son, daughter and grandson so that his great-grandson, Edgar, was able to receive the submission of both the Danish settlers and all the other English kingdoms and to be recognised as the first king of a united England at an elaborate coronation at Bath in 973. After them Saxon England, in the hands of weaker successors, fell under the increasing domination of the Danes until 1013 when Aethelred II, known as the ‘Unready’, had lost most of his kingdom outside traditional Wessex, and fled to Normandy before the attacks of an angry Sweyn, King of Denmark. Sweyn’s followers had swept right across Wiltshire in 1010 and 1011 and previously burnt Wilton in a lightning raid as early as 1003. The tide was almost turned by Aethelred’s son Edmund ‘Ironside’, who defeated Sweyn’s men at Penselwood and again at Sherston and was able to make peace with Sweyn’s son Cnut, but on Edmund’s mysterious death in the same year Wessex and the other kingdoms submitted to Cnut, who was now king of Denmark and Norway. Stability during Cnut’s reign was followed by some anarchy under his sons and then by the ascent to the throne of Edward ‘the Confessor’, half-brother of Edmund.

Wiltshire was not ignored by the late Saxon kings in their new grandeur and in reigns from Athelstan, who was buried in Malmesbury Abbey in 939, to Cnut they paid more formal visits to Wiltshire than to any other shire.

Edward the Confessor’s death in 1066 led to a dispute over the succession. The English councillors elected their fellow Harold, Earl of Wessex, in preference to Harold Hardrada, King of Norway, and to Duke William of Normandy who claimed the throne both as related to both Cnut and Edward and because (he said) he had been promised it by Harold of Wessex. The foreign claimants invaded England almost simultaneously; Harold of Wessex defeated Harold Hardrada in Yorkshire but was defeated and slain by the Normans near Hastings. Saxon and Wessex domination of England ended with him.

The Saxon legacy

Wiltshire still has a strong Saxon legacy: so much of the landscape in the patterns of fields and woods, the siting of villages and small towns, as well, of course, as the name, shape and very existence of the shire. In terms of monuments and art there is little to see beyond the largest of all, the Wansdyke and the Saxon burhs – Cricklade in particular. A large number of churches were built though most were of timber and have either decayed or been totally rebuilt, but two small and almost complete Saxon churches have survived in stone. The best preserved is that of St Lawrence, at Bradford, which, while mainly of the tenth century, is almost certainly successor to the one founded by St Aldhelm from Malmesbury in about 706. The other is a recent discovery at Malmesbury itself, a small chapel outside the West Gate, which had been used as a dwelling for some centuries. Of other church building only the tower at Netheravon shows unmistakable Saxon construction, but there are several excellent pieces of Saxon sculpture. These include the decorated arch at Britford, where Edward the Confessor heard of the Northumbrian rebellion in 1065, a unique cross-shaft at Codford St Peter carved with the figure of an ecstatic man holding an alder branch, which was considered pagan and subversive by Normans who buried it in a wall, and other cross-shafts at Colerne and Ramsbury. At Ramsbury are also two coped gravestones of Saxon bishops, for the church was a cathedral from 909 to 1058. At Knook is a tympanum carved with beasts in low-relief interlacing, rebuilt in a blocked south door, and at Inglesham is a tender relief of the Virgin and Child with the hand of God above. Of the beautifully decorated late-Saxon manuscripts of Malmesbury and Wilton Abbeys, few have survived. They were scattered at the Reformation and in the 17th century Aubrey’s schoolmaster at Leigh Delamere used them for wrapping his books.