A History of Northumberland & Newcastle Upon Tyne

The Landscape

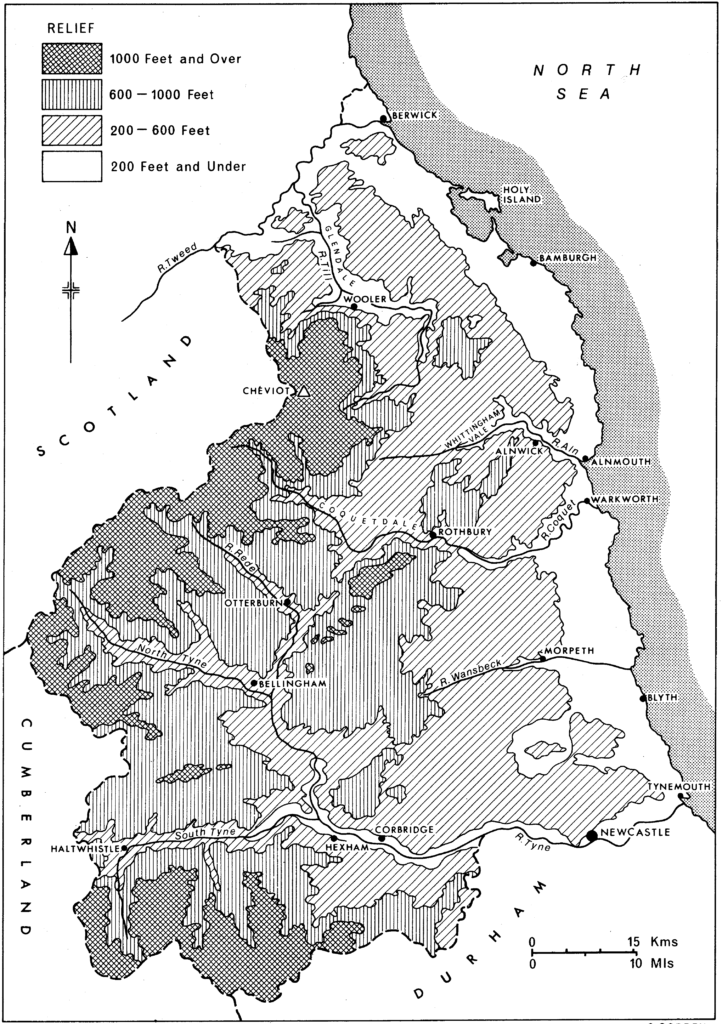

Northumberland is England’s northernmost county, and forms the major part of the border with Scotland. It was the last of the English counties to receive its modern form, for not until 1844 were the lands of North Durham (Norhamshire, Islandshire and Bedlingtonshire) incorporated into the administrative county. It was the fifth largest county, until the local government changes of 1974 detached its south-east fringe to form part of the new Tyne and Wear county. Yet the region has an historical unity that will not easily be destroyed by administrative changes. It has a varied landscape of shipyards and wooded river valleys, pit villages and windy moorlands. The magnificent coastline alternates between long, sandy beaches and rocky headlands. The boundaries of the county are well defined: the Tyne and Pennine foothills in the south, the Cheviots and border moorlands in the north-west, and the winding Tweed in the north. But although the boundaries are logical divides, and Northumberland is a clearer physical unit than most English counties, the historian should not make too much of them. If Anglo-Saxon and medieval history had gone differently in the north, as it might well have, the northern border could have been the Firth of Forth, or the Tyne the southern boundary of Scotland. The unity of Northumberland lies in the common experience of how history did go.

The highest ground is formed by the Cheviot Hills. The Cheviot itself, at 2,676 feet, is visible on a clear day from Newcastle, and in earlier times was an aid to navigation at sea. In the 1 7th century William Gray called it ‘a landmark for seamen that comes out of the east parts from Danzicke, through the Baltick seas, and from the King of Denmark’s countrey; it being the first land that mariners make for the coast of England’. The Cheviot granite is the stump of an ancient volcano, with rounded scenery of peat-bog and heather. Around it the ring of lavas support bracken and bent. This upland country must always have been largely open, a land of the sheep and the falcon, but not exclusively so, for in about 1538 Leland, the antiquary, wrote of ‘the great wood of Cheviot’ which was ‘spoyled now and crokyd old trees and scrubs remayne’.

The Northumbrian dales, moors and scarplands lie between the Cheviot Hills and the lowlands of the coast and Tyne. Around the Cheviot massif, where the volcanic lavas give way to the easily-eroded shales of the Cementstones, the scenery abruptly changes (at places like Alwinton and Ainham) to the broad, low-lying vales of the Coquet, Am, Breamish and Till rivers, and a landscape of farms, hedges and fields. These open valleys were settled early, and in medieval surveys they contained many of the richest villages in Northumberland, though the Till valley, littered with glacial sands and moraines, was (and still is) susceptible to flooding by the melting snows and summer rains. The Coquet is probably the finest valley (though many would argue for Whittingham Vale), and also a renowned trout-fishing river. Between these vales and the lowland plain are the resistant Fell Sandstones that form the scarplands of the Kyloe Hills, Ros Castle, and the Chillingham ridge, Corby Crags, the Simonsides and Harbottle Crag. These rocks make good building stones, and have been the main stone used for Northumbrian castles, churches and country-houses since Roman times. The scarps face in towards the Cheviots, and their summits provide some of the finest views in all Northumberland, though the fells themselves have thin, sandy soils and have been of little agricultural value.

In the south-west of the county the Cementstones and Sandstones are squeezed into a narrow belt along the border line, and the moorland scenery is made of the Carboniferous limestone that elsewhere lies under the coastal plain. Here the moors stretch to the horizon, broken only by occasional outcrops of sandstones, such as the Wannie, and the great volcanic dyke known as the Whin Sill that cuts through the Northumberland landscape from the south-west to the sea-coast and the Fames, with its most dramatic sections on the Roman Wall near Housesteads and on the coast at Dunstanburgh and Bamburgh. The valleys of the North Tyne and Rede cut through the moorlands, but they are narrow and much more cut off from the rest of Northumber¬land than the broad vales of the Coquet, Till and Am. This relative isolation of the North Tyne and Rede encouraged the development of a very wild and distinctive border society in the late medieval period.

The Northumberland lowlands stretch in a crescent around these moors and hills, from the border waters of the Tweed in the north, down the coast to Tynemouth and west along the Tyne valley. Here the solid rocks are generally overlain by glacial tills of clay and sand that give potentially good farming country, though south of the Coquet the clays of the coastal plain are heavy. The south-east corner is the economic heart of modern Northumberland. It forms an industrial triangle from Newcastle (which established its dominance over the economic life of the county in medieval times and has retained it ever since) down the Tyne to Tynemouth, then up the coast to Amble. Small coal seams occur near the surface in many parts of Northumberland, but the thick, rich seams that were the basis of the county’s industrial growth (and many of its 20th-century problems) lay under the boulder clays of south-east Northumberland.

The value of landscapes and regions alters with changing technology and circumstance, and before the expansion of coal-mining the southeast of the county was not a prosperous area, except for the immediate vicinity of Newcastle itself. The heavy clay soils were difficult for farming, and many areas only became useful after the introduction of underfield tile-draining in the 1840s and 1850s. The coastal plain north of the Coquet, with sandier, more loamy soils, was the prosperous, productive region of Anglian and medieval Northumberland. Similarly, the usefulness of the coastline itself has changed. The coast from Tyne to Tweed has few large harbours, and as early as the 1540s the King’s fleet had to anchor in the shallow water of Skate Road off Holy Island, yet in medieval and earlier times the tiny ships could use many of the bays and small harbours on the coast. Even Dunstanburgh Castle had its harbour, now a muddy stretch in front of the castle, cut off from the sea by shingle, where in 1514 the warships of Henry VIII took refuge.

Attitudes to the landscape have also changed, and our present appreciation of Northumberland’s moorland hills and coastal scenery was not always shared in the past. An 18th-century Rector of Elsdon, the Rev. Dodgson, was completely unimpressed by the moors of the Middle Marches, and when Vanbrugh built Seaton Delaval Hall in the 1720s he ignored the potential sea views the Hall could have had. By 1750 Tynemouth’s beaches and coves were already popular for the sea-air and bathing, but in about 1200 a monk from St. Albans thought very differently of the place: ‘Thick sea-frets roll in, wrapping everything in gloom. Dim eyes, hoarse voices, sore throats are the consequence’. He continued: ‘In the spring the sea-air blights the blossoms of the stunted fruit trees, so that you will think yourself lucky to find a wizened apple, though it will set your teeth on edge should you try to eat it. See to it, dear brother, that you do not come to so comfortless a place’. We ought, however, to remember the unglazed windows, bare stone floors and lack of good heating in medieval Tynemouth.

The present appearance of the Northumberland landscape is very largely man-made. The natural landscape was much more wooded than today, especially on the coastal plain and in the river valleys, though the analysis of pollen grains preserved in the peat-bogs of moorland Northumberland north of the Roman Wall has shown that many of these areas were also wooded, until forest clearance in Iron Age and Anglo-Saxon times. Clearing the woodland encouraged soil erosion, and river silting resulted, aided by man-made obstacles like weirs and fish-traps, which became a major problem on the medieval Tyne. The original landscape left after glaciation was very marshy and wet. Many place-names record this original state (such as Morwick, farm by the swamp), and numerous mires and lakes have been drained, the large Prestwick Carr near Ponteland as late as 1860.

There have also been natural changes in the environment. The river Coquet used to turn abruptly north at Amble before entering the sea, until in 1765 it cut the present mouth and left a long neck of dunes on the north side of the river as an isolated part of Amble township. In 1806 a storm caused a similar change at Ainmouth, when the river Aln shifted its mouth northward and cut the old church off from the village. The Northumbrian climate has been unstable. After the Norman Conquest the climate improved, with warmer weather and longer growing seasons, to an optimum about 1 150 to 1300. Cultivation was possible higher up the hills than it is today. Yet after 1300 the climate deteriorated and became colder and wetter. The margins of arable farming contracted downhill, and a study on the Lammermuir Hills, north of the border, has estimated that the upper limit of cultivation fell by 460 feet. This decline was gradual, though the appalling weather of 1315-17 provides a good starting date. After 1550 there was a further decline into what is known throughout Europe as the ‘Little Ice Age’, and only after 1700 did the climate improve. One must therefore sympathise with the Tudor officials sent north from London who complained about the Northumbrian weather. The poor Duke of Norfolk, who suffered from chronic diarrhoea, begged the King in October 1542 not to make him winter in the cold of Alnwick ‘for assuredly I know if I should tarry in these parties it should cost me my life’. In December 1595 Lord Willoughby, governor of Berwick, wrote ‘if I were further from the tempestuousness of Cheviot Hills and were once retired from this accursed country, whence the sun is so removed, I would not change my homliest hermitage for the highest palace’. Six months later he died of a great cold and fever. Fortunately, the present Northumbrian climate is considerably pleasanter.